There's little argument that fueling athletic efforts, whether it be outings in the mountains or competitive endurance events, has become increasingly simple over the last two decades. When I first started bike racing in the mid '80's, figuring out what to eat to get through a 4 hour race was tricky. In training, I was eating Pop Tarts and Sweet Tarts, the latter being mostly maltodextrin, a good source of complex carbohydrate which, at the time, was gaining some noteriety in endurance nutrition. But using this stuff while racing was not straight forward. Hell, I didn't even know how many calories I needed each hour to keep from bonking.

There's little argument that fueling athletic efforts, whether it be outings in the mountains or competitive endurance events, has become increasingly simple over the last two decades. When I first started bike racing in the mid '80's, figuring out what to eat to get through a 4 hour race was tricky. In training, I was eating Pop Tarts and Sweet Tarts, the latter being mostly maltodextrin, a good source of complex carbohydrate which, at the time, was gaining some noteriety in endurance nutrition. But using this stuff while racing was not straight forward. Hell, I didn't even know how many calories I needed each hour to keep from bonking.

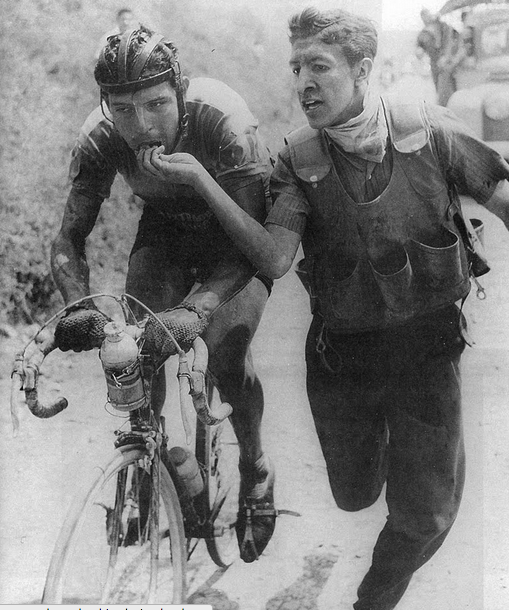

What's in those bags??When I started going to high profile professional races where amatures could compete, as well, I started paying attention to what the pros were eating. No big revelations here. Just cookies and granola bars and stuff like that. Drink mixes were starting to become popular and I remember the first Power Bar in 1987. None of this stuff, except for the drinks, was easy to eat while going hard. I remained perplexed. Even looking at what the Euro dogs were eating didn't help. These guys were sucking down ham and cheese sandwiches, ferchrissakes. Where's the mystery of science in that?

What's in those bags??When I started going to high profile professional races where amatures could compete, as well, I started paying attention to what the pros were eating. No big revelations here. Just cookies and granola bars and stuff like that. Drink mixes were starting to become popular and I remember the first Power Bar in 1987. None of this stuff, except for the drinks, was easy to eat while going hard. I remained perplexed. Even looking at what the Euro dogs were eating didn't help. These guys were sucking down ham and cheese sandwiches, ferchrissakes. Where's the mystery of science in that?

One memorable experiment involved a 100 mile road race in Everett, Washington that took place on a 10 mile circuit. I decided I would do the whole 4 hours on liquid calories alone. Cytomax and Exceed were the two main drinks around then and I did about 5 bottles of Cytomax. I felt great and performed well. This was eye opening. This was also around the time the Gatorade Sports Science Institute was doing a lot of research on gastric emptying and absorption of various concentrations of carbohydrate containing drinks. The military was also involved. Some crazy recommendations came out about fluid and electrolyte replacement during this time that have influenced how athletes feed during training and racing to this day.

In 2012, Dr. Tim Noakes, a South African exercise science expert and researcher, published "Waterlogged", a intensely researched treatise on the myths and misunderstandings that led to the recommendations mentioned above. I encourage everyone to read this important work. It'll challenge everything you thought you knew about hydration and fueling for athletics. The most significant point of the book concerns hydration and what we think we know about it. But Noakes also confirms that the most important aid to endurance performance is adequate carbohydrate intake.

In 2012, Dr. Tim Noakes, a South African exercise science expert and researcher, published "Waterlogged", a intensely researched treatise on the myths and misunderstandings that led to the recommendations mentioned above. I encourage everyone to read this important work. It'll challenge everything you thought you knew about hydration and fueling for athletics. The most significant point of the book concerns hydration and what we think we know about it. But Noakes also confirms that the most important aid to endurance performance is adequate carbohydrate intake.

Choices

Any visit to the nutrition section at REI will confirm that we have a lot of options when it comes to training and racing fuels. Many claim to have unique ingredients that give them an edge over their competitors. The merit of these claims is certainly up for discussion beyond the scope of this post. What all of them have in common is some form of carbohydrate. You can drink it from your water bottle, slurp it out of a gel packet or chew it from a bar but the idea is to keep the carb calories coming in at about 200-300 calories an hour. I discuss the specifics of this concept here.

Any visit to the nutrition section at REI will confirm that we have a lot of options when it comes to training and racing fuels. Many claim to have unique ingredients that give them an edge over their competitors. The merit of these claims is certainly up for discussion beyond the scope of this post. What all of them have in common is some form of carbohydrate. You can drink it from your water bottle, slurp it out of a gel packet or chew it from a bar but the idea is to keep the carb calories coming in at about 200-300 calories an hour. I discuss the specifics of this concept here.

Over the years, companies have added protein, specific amino acids and certain fats to the mixes in hopes of gaining further benefit. The results have been mixed at best. But there's no questioning the benefit of sugar and its cousins for enhancing performance and delaying fatigue. And with the advent of all these products, especially gels, it's never been easier to get what you need. I remember when GU first came out and how relieved I felt that I'd never have to mess around with the food issue again. Never again would I have to spit out anything as I tried to swallow something when a competitor would attack in a race.

Over the years, companies have added protein, specific amino acids and certain fats to the mixes in hopes of gaining further benefit. The results have been mixed at best. But there's no questioning the benefit of sugar and its cousins for enhancing performance and delaying fatigue. And with the advent of all these products, especially gels, it's never been easier to get what you need. I remember when GU first came out and how relieved I felt that I'd never have to mess around with the food issue again. Never again would I have to spit out anything as I tried to swallow something when a competitor would attack in a race.

Now, many of you outside of competitive circles who simply climb and ski for fun shake their heads at those of us sucking "fake food" out of little packets and bottles. You guys would rather eat a sandwich or even a candy bar to get the calories you need. And for people not in a hurry, this actually works fine. The problem is that when your metabolic output goes up we rely more and more on carbohydrate to fuel the effort. Once you're breathing hard enough so that conversation is difficult, glycogen (sugar), becomes the preferred substrate for the effort.

If you're noodling along talking with friends you're burning mostly fat and most humans have nearly an unlimited store of this. As the pace increases, so does the percentage of carbohydrate required to sustain the effort. Some athletes can stave off the transition to mostly carbohydrate metabolism longer than others. Diet and training can delay this point even further. But once you punch it, better keep sucking down the gels or you're going to have to slow down sooner than you'd like.

Pierra Menta Fueling

As most of you know, I spent 2 months of this spring camped in Chamonix, France, skiing the mountains of my childhood dreams. As a former competitive ski mountaineer, being in the same time zone as the sport's premier event proved too enticing for me to ignore. Along with my equally psyched partner, Nate Brown, from Wilson, Wyoming, we enjoyed four days of some of the best ski racing either of us have ever experienced.

There are numerous stories of skimo champions finishing 2-3 hour events having sucked down only a gel or two, sometimes even nothing. A combination of cold and sustained effort often sees mid-race nutrition completely neglected. But the PM is a notoriously strenous event involving about 3,000 meters of climbing each day over the course of around 4 hours. No one is going to get through four days of that forgetting to eat.

Luckily, the temps were warm so freezing food was not an issue. I had a bladder to wear under my suit and planned less than a liter of water each day. I wanted to go straight water so as to not confuse my calorie intake. I had enough GU for the event. In order to closely monitor my intake, I decided to use a single water bottle and put all my calories in there for each day. As most of you know, I like my GU diluted so it's easier to get down and travels better in the cold. I could get through the first hour of each day on the calories from breakfast and a prestart handful of Chomps.

After that, I needed, on average, 12 to 16 gels in the bottle with the rest water. I drank one quarter of the bottle each hour, usually in a few sips over the 60 minutes. Nate and I were on each other at each transition about eating and Nate often barked elapsed time to me on the skin track to help me remember my ration. It worked great.

I honestly don't know why athletes try to complicate the fueling of their efforts, whether racing or otherwise. Once again, the simple formula outlined in these pages continues to deliver. I arrived at the finish each day feeling great, never hungry and more than psyched for the next day's effort. And when I'm out on a mission trying to get more vert and ski more powder than anyone on the hill, these same tactics keep me moving and shredding all day. I'll save the chewing for the chips in the car on the way home.